3.3 Co-management of Caribou

Co-management of wildlife resources is an approach to wildlife management where multiple stakeholders work together and share expertise and knowledge to make recommendations concerning management protocols and standards. Stakeholders often include Indigenous communities, municipal governments, provincial/territorial governments, and federal governments. Wildlife co-management approaches have been undertaken in both aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. This section provides an introduction to caribou co-management boards in the Canadian North before discussing knowledge holders on co-management boards and issues and limitations with the process.

Introduction to Caribou Co-management Boards

Historical Development

Discussions and plans to open the Canadian Subarctic and Arctic to development grew with increasing intensity in the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1958 federal election campaign, a major part of John Diefenbaker’s strategy was “The Vision” for the North:

This vision to open up the North was not without problems. Canada had not settled land claims or treaties in many areas of the country. As proposals for oil pipelines, hydroelectric dams, mining and oil exploration, and other projects piled up, First Nations, Inuit, and Metis peoples expressed their political might that such projects would not continue without first settling land claims and including their involvement in the evaluation and planning process for development. In 1973, the Supreme Court of Canada made a decision in the Calder v. Attorney-General of British Columbia case (concerning the Nisga’a First Nation’s claim to land) that Aboriginal title to land exists, which forced Pierre Trudeau’s federal government to begin the modern comprehensive land claims negotiation process.

The land claims negotiation process is very complex, and its intricacies are beyond the scope of this module. However, Indigenous communities in the North wanted to fully participate in wildlife management decision making. Previously, all too often, decisions like hunting restrictions had been made without the involvement of Indigenous communities, often to the detriment of those communities.

Contentious issues existed between “indigenous peoples’ traditional relations with animals, proposals for industrial development, and natural scientists’ quest to advance knowledge of wildlife” (Kofinas 2005:179). These issues related to colonialism, ways of knowing the world and caribou, and power and property relations. Co-management was proposed as an approach to reduce conflict and bring together different interested parties to better manage wildlife resources. In the 1980s, several co-management agreements were legislated by provincial/territorial, federal, and indigenous governments to create co-management boards that would guide decision-making on wildlife management. For example, the Beverly and Qamanirjuaq Caribou Management Board was created in 1982, and the Porcupine Caribou Management Board was created in 1985.

Purpose of Caribou Co-management Boards

Co-management boards are meant to safeguard the wellbeing of caribou herds now and into the future. Part of this includes creating regulations that continue to allow humans to hunt caribou without severely impacting the overall health of caribou populations. In order to do this, caribou co-management boards include a variety of representatives from different communities and governments that work together to achieve the following:

- Power-sharing between “state” and “indigenous systems” (Kofinas 2005:180)

- More holistic insights into ecosystem dynamics through the “integration of traditional and science-based knowledge” (Kofinas 2005:180)

- Lower enforcement costs indigenous communities self-regulating management standards

Co-management Knowledge Holders

Co-management boards often include representatives from First Nations, Inuit, and Metis communities; non-Indigenous local community members with interests in wildlife resources (e.g., hunting and fishing outfitters, environmentalists); provincial/territorial government wildlife managers; and federal government wildlife managers.

As explained Section 3.1, different people bring different experiences and knowledge about caribou to the boards. One of the claimed benefits of co-management is that people with different knowledge about caribou can share their knowledge to come up with holistic understandings of caribou and their ecosystems to create better management standards. First Nations and Inuit communities can bring their extensive knowledge from hunting and interacting with caribou throughout the year for many generations to the table, while wildlife biologists can bring their standardized scientific understandings of caribou. Other groups like hunting outfitters and environmentalists also have unique insights into caribou and are sometimes included on co-management boards.

Please see the following web pages for examples of caribou management board organization:

Porcupine Caribou Management Board (see diagram halfway down the page)

Beverly and Qamanirjuaq Caribou Management Board

Issues and Limitations with Co-management

Co-management boards are made up of representatives of a variety of different people and groups. Differences between the groups have revealed some issues and limitations to the co-management system. Some of these are presented here. What other limitation do you think might exist with such a system?

Respect Towards Animals

The way that wildlife biologists conduct research and come to know caribou has, at times, been called into question by First Nations and Inuit communities. Many First Nations and Inuit people believe that animals present themselves to be hunted when they are ready to be caught (Fienup-Riordan 2003; Kofinas 2005:185; Nadasdy 2003:83-94). In a sense, they give themselves to the hunter. However, hunters are obliged to respect the animal in the way it is hunted and prepared after hunting. This is part of the reciprocal exchange that will ensure animals give themselves in the future. Bothering or playing with animals is not considered to be respectful, and some ways that scientific research is conducted is seen as playing with animals.

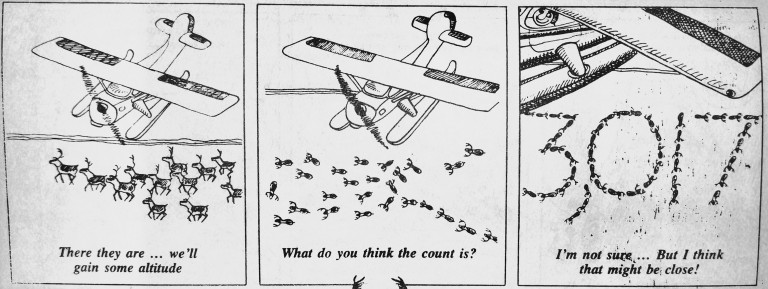

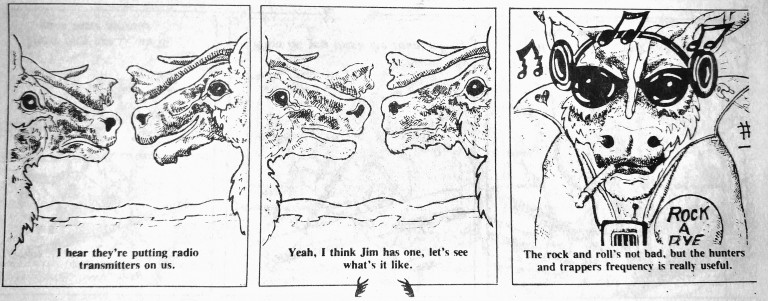

For example, Gary Kofinas (2005) presents a controversy that arose in 1993 when two teams of caribou biologists were staging their research out of the Vuntut Gwitchin community of Old Crow, Yukon. The biologists were using boats, helicopters, a fixed wing aircraft, radio telemetry equipment, and a net to capture caribou cows and calves and record body condition data and survival rate data. Members of the Vuntut Gwitchin community became incensed about the way research was done as it was seen as “playing with animals.” Board members on the Porcupine Caribou Management Board as well as non-board members from the community called for a moratorium on caribou research in the region. After some tense conversations and negotiations, it was eventually decided that research could continue, but biologists needed to have better communication about their research with the community and calf collaring would be phased out of the research agenda.

Fragmentation of Indigenous Knowledge in Caribou Management

In “Yukon Arcadia: Oral Tradition, Indigenous Knowledge, and the Fragmentation of Meaning,” Julie Cruikshank (1998) relates an account of Mrs. Annie Ned, a Southern Tutchone Elder, standing up in a conference and talking about how disconnected scientific and resource management understandings of caribou were from stories about caribou that she learned by listening to her Grandpa. Cruikshank wonders how Mrs. Annie Ned’s knowledge learned from her Grandpa could ever be used as TEK for resource management and other purposes.

So often, in order for indigenous experiences and knowledge to be used in co-management, it has to be presented in a form that is comparable with scientific data. This process of transformation requires what Paul Nadasdy (1999) has called “compartmentalization” and “distillation” of knowledge. Compartmentalization involves breaking knowledge from its social contexts and presenting different aspects of it in separate categories. Distillation involves keeping only the knowledge that is suitable with existing scientific data.

Inevitably, a lot of the context and significance of indigenous knowledge is lost. The loss and transformation of knowledge to make it compatible with other forms of knowledge is a complexity that caribou co-management boards must consider.

Bureaucratization

In “Yukon Arcadia: Oral Tradition, Indigenous Knowledge, and the Fragmentation of Meaning,” Julie Cruikshank (1998) relates an account of Mrs. Annie Ned, a Southern Tutchone Elder, standing up in a conference and talking about how disconnected scientific and resource management understandings of caribou were from stories about caribou that she learned by listening to her Grandpa. Cruikshank wonders how Mrs. Annie Ned’s knowledge learned from her Grandpa could ever be used as TEK for resource management and other purposes.

So often, in order for indigenous experiences and knowledge to be used in co-management, it has to be presented in a form that is comparable with scientific data. This process of transformation requires what Paul Nadasdy (1999) has called “compartmentalization” and “distillation” of knowledge. Compartmentalization involves breaking knowledge from its social contexts and presenting different aspects of it in separate categories. Distillation involves keeping only the knowledge that is suitable with existing scientific data.

Inevitably, a lot of the context and significance of indigenous knowledge is lost. The loss and transformation of knowledge to make it compatible with other forms of knowledge is a complexity that caribou co-management boards must consider.

References Cited

Berkes, Fikret. Sacred ecology, 3rd ed. Routledge, 2012.

Cruikshank, Julie. “Yukon Arcadia: Oral tradition, indigenous knowledge, and the fragmentation of meaning.” The social life of stories: Narrative and knowledge in the Yukon Territory, 45-70. UBC Press, 1998.

Fienup-Riordan, Ann. “Original ecologists?: The relationship between Yup’ik Eskimos and animals.” Eskimo essays: Yup’ik lives and how we see them. Rutgers University Press, 2003.

Kofinas, Gary P. “Caribou hunters and researchers at the co-management interface: emergent dilemmas and the dynamics of legitimacy in power sharing.” Anthropologica 47, no. 2 (2005): 179-196.

Nadasdy, Paul. “The politics of TEK: Power and the ‘integration’ of knowledge.” Arctic Anthropology 36, no. 1/2 (1999): 1-18.

Nadasdy, Paul. Hunters and bureaucrats: power, knowledge, and aboriginal-state relations in the southwest Yukon. UBC Press, 2004.